The Return of the Enemies

Epping shows how quickly a legal judgment can be twisted into a populist parable about migrants and traitorous judges.

The Court of Appeal’s judgment in the Bell Hotel case, Epping, was one of those narrow rulings that only lawyers care about. The High Court had granted an injunction to stop asylum seekers being housed in the disused hotel; the appeal court found the judge had erred in law. That was it. Yet by late afternoon,

Robert Jenrick had written a Telegraph column warning that ‘Starmer is on the side of illegal migrants, not the British people.’ Kemi Badenoch accused Labour of ‘ignoring’ residents. Nigel Farage announced that asylum seekers had more rights than ‘the people of Essex.’ The mechanics of judicial review (dull, procedural, nothing to do with politics) had become another front in Britain’s permanent culture war.

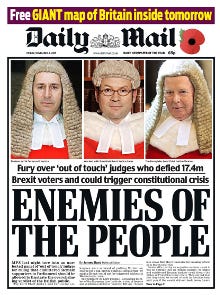

This wasn’t new. We have been here before. In November 2016, when the High Court ruled that Article 50 couldn’t be triggered without parliamentary approval, the Daily Mail printed photographs of three senior judges across its front page under the headline ‘Enemies of the People.’ Then as now, the legal ruling was minimal: a question of process, not substance. Then as now, the right framed it as a betrayal.

The continuity matters, but so does the difference. The Brexit-era attack on judges was about sovereignty, about the spectre of a technocratic class blocking the “will of the people.” The new attack is about security, about the supposed betrayal of ordinary Britons in favour of “illegal migrants.” In both cases the target is the same (the judiciary, as the institution that refuses to align itself uncritically with executive will) but the terrain has shifted. Brexit is over; the enemy within has been redefined.

The right has always had a gift for reframing defeat as betrayal. The Epping case is useful because it allows them to rerun the Brexit script, only with a new cast of villains. The hotel ruling didn’t grant asylum. It didn’t even determine the legality of housing migrants in Epping. It simply said the lower court had misapplied the law. But what matters is the narrative space it opens: the chance to tell a story in which faceless judges shield “predatory men” from “ordinary people,” and in which Labour, by failing to denounce the ruling, is complicit.

Dialectically, what we are seeing is the reversal of roles. The judiciary, one of the most conservative institutions in the British state, is being cast as an insurgent force undermining order, while Farage, Jenrick, and Badenoch, the tribunes of reaction, present themselves as defenders of democracy. This inversion only works if “the people” is narrowly defined: not those who live in Britain, but a constructed community of white, nativist belonging. Essex becomes a synecdoche for Britain itself. To stand with Essex is to stand with the nation; to stand with asylum seekers is to stand outside it.

The irony, if that’s the word, is that the courts are doing exactly what conservatives once insisted they should do: interpreting statute with minimal interference, sticking to precedent, avoiding politics. But when the result is inconvenient, neutrality itself becomes intolerable. Judicial independence, in this schema, is not a virtue but a betrayal. The lesson of Brexit has been fully absorbed: if the law does not serve, the law must be attacked.

This is where the real danger lies. Populist attacks on courts are not just rhetorical flourishes. They alter the balance of forces. Every time the right tells people that judges have “sided with migrants,” it makes judicial restraint politically impossible. Either the courts bend towards executive preference or they are denounced as treacherous. The rule of law becomes a hostage to nationalist affect.

It is worth recalling that the 2016 “Enemies of the People” headline produced outrage among liberal elites but very little in the way of political defence for the judiciary. May’s government remained silent; Labour, already consumed by internal war, said little. The same pattern is repeating. Starmer’s government will not expend political capital defending judicial independence when it risks being accused of “siding with illegals.” Silence, in this case, is complicity.

One can almost hear the machinery grinding: a future in which the right calls for reforms to make it easier to overrule judicial review, or for new emergency powers in the name of protecting “the people.” The logic of the rhetoric demands escalation. Once you declare that the law itself betrays you, only force remains.

The dialectic is merciless. The right invokes “law and order” while undermining law; it claims to speak for “the people” while narrowing the category to exclude millions; it presents itself as defending democracy while turning every mediating institution (courts, universities, even Parliament) into enemies. The substance changes (sovereignty yesterday, asylum today) but the form is constant. Every obstacle is betrayal, every defeat is conspiracy, every institution that fails to deliver is illegitimate.

In the end, the question is not what the judges decided in Epping, but whether we are willing to recognise the pattern for what it is: a systematic campaign to dismantle the very institutions that make politics more than mob rule. That campaign is old, and it is working.